By Yedida Kanfer, PhD

In 1899, Polish writer Wladyslaw Reymont wrote a book entitled The Promised Land. Its subject was the city of Lodz, the “Polish Manchester,” which boomed as a textile center of the Russian Empire in the late nineteenth century.

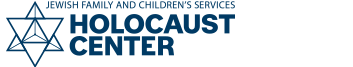

Poznanski factory in Lodz, Poland (left) and Izrael Poznanski

Reymont intended the title of his book to be sardonic, a critique of the excesses of a wealthy few and the poverty that accompanied industrialization. Nevertheless, it reflected a reality shared by Lodz and the other rapidly growing, multi-ethnic cities of Eastern Europe: they offered a multitude of promises to the migrants who flocked to them. In Lodz, Jewish and ethnic German factory owners presided over the city’s industry and did so with pragmatic cordiality. The city’s workers—Poles, Germans, and Jews—joined an array of movements that offered them hope of various Edens, whether socialist or national.

Of course this period of ethnic coexistence did not last forever: discrimination against Jews (and other minorities) increased in Poland after World War I, and antisemitism found its culmination in the Holocaust. After the war, Soviet rule forcefully subsumed all difference in Eastern Europe, Poland included, under the communist banner.

The collapse of the Soviet Union (1989-91) opened the door for ethnic and religious reconciliation and solidarity, however, this occurred differently in each former Soviet state. For Poland and its neighbor Ukraine, the differences in each country’s postwar experience created diverse engagements in Holocaust memory and history.

Poland: The Promise of Public Engagement with the Past

Yedida Kanfer with a statue of Izrael Poznanski

After the Holocaust, the majority of Jews in Poland either emigrated or suppressed their Jewishness. What had been a thriving population of 3 million in 1939 numbered in the few thousands in the early twenty-first century.[1] As I wandered the city streets of Lodz as a graduate student in 2007, I found reminders of the town’s once numerous Jewish inhabitants everywhere I went. In the above photo, my arm is wrapped around a statue of Lodz Jewish industrialist magnate Izrael Poznanski (1833-1900). I am smiling not because I am particularly happy but rather because the act of posing for this picture is the realization of an ideal. To use the term of anthropologist Erica Lehrer, this was the recreation of a “Jewish space” in Poland, one that bridged the past and present.[2]

My heady idealism was a product of a specific time and constellation of historical events. At the time of my visit, it had been over 20 years since Poland had shaken off the yoke of Communist rule along with its state-sponsored antisemitism and public amnesia about the Holocaust. In the years prior to my arrival in Lodz, and in the decades thereafter, Poland took up the question of the responsibility of Poles for crimes against Jews. The publication of Neighbors, in which Jan Gross wrote that in the town of Jedwabne in 1941 “half the population of a small East European town murdered the other half–some 1,600 men, women, and children,” raised the question of what would come next in Polish-Jewish relations. In Yael Bartana’s 2007 film Mary Koszmare (Nightmares), Polish intellectual Slawomir Sierakowski cried out for Poland’s lost Jews to “return to Poland, to your homeland and to ours.” Five years later, in Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places, Erica Lehrer articulated the hopes of many young Poles and Jews in aspiring towards Polish-Jewish reconciliation. Given the small number of Jews in present-day Poland, Lehrer argued, “heritage sites” (such as the Poznanski statue) could serve as the basis for dialogue. This was a vision of a “healing” Poland, one that aspired to diversity, to be a model of cosmopolitanism in Eastern Europe.

Ukraine: The Promise of Unified Individuality

While Sierakowski was making grand overtures to Poland’s lost Jews in 2007, post-Soviet Ukraine to the east was plagued by the rule of oligarchs, widespread corruption, and electoral fraud. In November 2013, after Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych recanted on plans to sign an agreement with the European Union, protestors began to camp out on Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square). When riot police and state-hired thugs began to use violence to disperse the crowds, what had started as a protest quickly became a revolution. Support for the “Euromaidan,” as the protests were known, came from all over Ukraine, and demonstrators on the Maidan Nezalezhnosti endured freezing weather and brutal violence until Yanukovych fled the country on February 21.

Participants described the Euromaidan as “an alternate world, ‘passionate and motley in its social and ideological composition.’” Intellectuals joined peasants, and Jews stood in the same crowd as members of the Ukrainian national far Right. Historian Marci Shore, who conducted extensive interviews with Maidan activists, noted a common theme: The realization that a line had been crossed. “All of them experienced a moment when it was imperative to make a choice. This was ‘choosing’ in the strongest, existentialist sense described by Jean-Paul Sartre [….] Time and time again I heard, in different languages, ‘it was my choice.’” The fall of the Soviet Union had sounded the death knell for the overarching ideologies born in the nineteenth century. What was there to take their place? Post-Soviet Ukraine had not enjoyed the full benefits of a public exchange of ideas; it had lacked Poland’s community of discourse. Shore argues that in Ukraine, the act of making a choice engendered a sense of “selfhood,” or self-realization. This new subjectivity, paradoxically, brought people together in the remarkable solidarity of the Maidan.[3]

The Challenges to Our Promised Land

The cosmopolitan hopes of post-Soviet Poland and Ukraine are now in jeopardy. As a response to the Maidan protests in 2014, Russian president Vladimir Putin occupied the Crimea (a Ukrainian peninsula that borders Russia), sent unidentified militias to invade Eastern Ukraine, and intensified a propaganda war in the newly occupied territories that challenged the very notion of “truth.”[4] In January 2018, a right-wing nationalist government in Poland criminalized any public statement that would hold the Polish nation or state complicit in Nazi crimes. Although components of the law have since been rescinded, the state challenge to freedom of expression—both in private and public—remains intact.

With the Jewish New Year around the corner, a time of individual and communal reflection, I think about my own choices. Historian Timothy Snyder has said about the world of post-truth: “What we do every day matters, and most important is to accept that responsibility.” And so I think, about my hopes for society, and my goals for myself. As I embrace the Lodz of Izrael Poznanski, I stand together with my Polish colleagues who protest on the streets of Warsaw: “Jedwabne, too, is part of my Poland.”

[1] It is hard to estimate the number of Jews in Poland today. In 2006, less than 4,000 Jews had registered with Jewish organizations, but there were likely tens of thousands of Jews in total. See: Kozlowski, et al, Difficult Questions in Polish-Jewish Dialogue (Warsaw, 2006), 174-5.

[2] Erica Lehrer, Jewish Poland Revisited: Heritage Tourism in Unquiet Places (Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2013). Lehrer borrows the term “Jewish space” from Diana Pinto (see p.2).

[3] Marci Shore, The Ukrainian Night, The Ukrainian Night: an Intimate History of Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), xiv-xvi, 44, 51-3, 269-70.

[4] Shore, The Ukrainian Night.