By Shayna Dollinger, Pell University Fellow at the JFCS Holocaust Center

Coffee is one of the oldest luxuries and strongest addictions. From Costa Rica to Tanzania and all across the globe, coffee tells stories.

But what stories does coffee tell about one of the darkest periods in Jewish history?

Coffee first arrived in Europe in the 17th century and soon became a continental phenomenon. But by the end of the First World War, once the allied forces blockaded German ports, a coffee shortage flooded Germany. The Nazi party levereged this shortage in their favor. Caffeine, they claimed, would inhibit the possibility of a perfect, healthy Aryan race. In fact, the inventor of decaffeinated coffee, Ludwig Roselius, was a loyal Hitler supporter. His coffee, Kaffee Hag, was served at government meetings and Hitler Youth rallies as a means to achieve “Leistung,” or high achievement. In a 1941 Hitler Youth handbook, caffeinated coffee is called “poison in every form and in every strength.” Decaf coffee played a large role in the commercial world of Nazi Germany, advertised as a way to stay healthy and strong. Thus, Germans turned to decaf coffee to preserve their own racial purity and power.

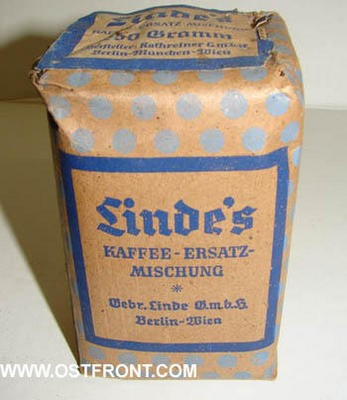

For Jews, the coffee shortage made life in Ghettos all the more challenging. Jews confined to Ghettos were given ration cards. The coffee granted by these ration cards was not the strong, dark and (for many) delicious coffee that we drink today. Instead, Jews were allowed a cup of what was called ersatzkaffee, German for “substitute coffee.” This warm liquid resembled coffee in its color but in little else. It was made from materials that could be easily found in Germany and Poland at the time. Most often, it consisted of ground up chicory root but could also be found made of malt, barley, rye, and acorn.

Once sent to concentration camps, such as Auschwitz and Treblinka, prisoners were allowed one cup of ersatzkaffee as their breakfast each morning, occasionally along with bread. Henry Libicki, a survivor who spent time at multiple camps explained in his oral history interview that “Coffee wasn’t coffee, coffee was… ‘ersatz,’ substitute. Everything was ersatz…. Coffee was made out of grain, burned grain, that was coffee. Tasted like ink, that was the best you had.” For Jews, coffee was used as a tool of oppression.

While the Nazis drank decaffeinated coffee as a means to stay healthy, Jews were given fake coffee as a means of humiliation. Thus, coffee became an illustration of power in Nazi Germany, a social construction. For Nazis it was luxury, while for Jews it was punishment. And the Nazis had the power to determine its meaning.

So when you drink your coffee each morning, think about the history that lies in each sip.

References

http://www.ww2incolor.com/modern/Linde__sErzatz.html

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Coffee_substitute

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/decaf-coffee-nazi-party

https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30087750

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/chicory-coffee-mix-new-orleans-made-own-comes-180949950/

https://collections.ushmm.org/oh_findingaids/RG-50.477.0713_trs_en.pdf

https://www.berfrois.com/2011/06/s-jonathan-wiesen-decaffeinated-nazis/